Knowledge Centre- Subject Index Main Help page |

Aerial Photography

by Tim Slater

Part 1 - The Pre-Cursor 1849 to August 1914

Part 2 - The Beginnings August 1914 to January

1916

Part 3 - Aerial Photography comes of age

Part 4 - The Uses for Aerial Photography

Part 2 - The Beginnings August 1914 to January 1916

The early weeks of the First World War were a war of movement, and during this stage the aircraft on all sides performed about as expected, as long range scouts keeping commanders appraised of the enemy’s strategic movements. Following the First battle of the Marne (6-9 September 1914) the character of the war began to change, aerial reconnaissance began to shift from recording movement to surveillance and artillery direction. On 15 September 1914 Lieutenant G. F. Pretyman, a pilot from 3 Squadron, took five photographs of German artillery positions on the Aisne with his own hand held camera (Eaton, APIS Soldiers with Stereo. p. 3.). Although of dubious quality they demonstrated that aerial photography was possible in a combat environment. During First Ypres with aerial photography still failing to impress, sketch maps of enemy trenches and gun pits located by aerial reconnaissance were issued by GHQ intelligence. The stalemate of the trenches brought new challenges to aerial surveillance. Surveillance required repeated flights, over both the immediate front and well to the rear, to detect changes to the German dispositions, and any movement or build-up of forces or logistics. Whilst flights monitoring German rail, road and river movement could be captured by the human eye and noted down the German’s intricately evolving trench systems proved more problematic. Only the camera could provide the definitive view corroborating or correcting the aircrew’s visual observations.

At this stage of the war the impetus for aerial photography innovation rested at the junior officer level. Lieutenant Charles Curtis Darley, a Royal Artillery (RA) officer serving as an observer in the RFC, was the most enthusiastic photographer in 3 Squadron.

‘At first we had, I think, one Aeroplex camera only, and the results were poor, due to fogged plates and being scratched on the film surface due to the metal plate holders. I don't think anyone else in the squadron except myself did any photography at this time. Later Lieutenant E Powell may have taken some. I had to buy my chemicals in Bethune, develop the slides in an emergency darkroom we made up in the stables of the chateau in which we were billeted and send them out.’ (The National Archives, AIR 1/2395/255/1, 3 Squadron notes on aerial photography. 1914 Dec. - 1915 Feb)

During the autumn of 1914 Darley had set up a dark room in the stables of a château where the squadron was billeted and purchased chemicals from Béthune for photographic processing. Initially using his own Aeroplex camera, and then a Pan Ross camera borrowed from a Lieutenant C. D. M. Campbell (who will be discussed later), he slowly collected photographic coverage of the German lines on the Fourth Corps front and following processing painstakingly assembled all the photography to build up a mosaic of the German defence system. On this photographic map he carried out the interpretation and identified and annotated all the salient points of interest, showing the latest developments in the German defensive positions. The mosaic, completed during January 1915, was intended for use by the squadron for planning and reporting purposes but the squadron commander, Major J. M. Salmond, was so impressed that he took it to Corps Headquarters (Eaton, APIS Soldiers with Stereo. p.3.). Darley described the process in his notes:

‘I made a trench map showing all the trenches on our and the enemy sides from the La Bassee - Bethune Road south of the brickfields, including the railway triangle to the north of Neuve Chapelle almost to the Aubers Ridge, which was the limit of the 3 Squadron area. The accurate part of the map finished north of Neuve Chapelle... This I believe was the first trench map and though I made it for my own use as an observer, Major Salmond took it to, I think, Indian Corps H. Q., where it excited considerable interest as shewing the possibilities of aerial photography, and translating the photographs, which were meaningless to most officers, to an intelligible map.’ (The National Archives, AIR 1/2395/255/1, 3 Squadron notes on aerial photography. 1914 Dec. - 1915 Feb)

The mosaic created quite a stir as it clearly illustrated:

‘. . . how the information on the photographs could be reproduced in a form intelligible to all officers.’. H. A. Jones, The War in the Air Volume 2 (Oxford, Clarenden Press, 1928) p. 89.

Here was a picture showing the enemy dispositions that a General could relate to and understand. The detail the photographs provided and their ability to bring the front immediately to the map table made converts of those who where to use it. It would not be long before the interpretation of aerial photographs became an essential element of battle planning.

With the onset of trench warfare and the corresponding change in the tempo of operations, the British corps commanders Generals Haig and Smith-Dorrien began calling for RFC squadrons to be put at their disposal for observation and photography work. When the BEF formally split into two armies on 26 December 1914 the RFC decentralised. By January 1915 it had been split into an RFC HQ and two RFC Wings, comprising of a least two Squadrons and commanded by a full Colonel, each allocated to an Army. First Wing, allocated to Haig’s First Army, was commanded by then Colonel Trenchard. Sholto Douglas a young recently transferred Royal Horse Artillery subaltern continues the story:

‘When I joined 2 Squadron, RFC early in 1915, there was practically speaking no such thing as air photography. I was told that a few photographs had been taken on the Marne by one or two enterprising officers, but these were purely private ventures. However, soon after.... Hugh Trenchard came out to take over 1 Wing, a camera appeared in the squadron, together with a civilian disguised as a Corporal, RFC. This would be sometime in February 1915. The various observers in the squadron were canvassed with a view to finding out whether any of them knew anything about photography. I had a camera as a boy, and had taken, developed and printed some very amateurish photographs. On the strength of this, I was appointed the squadron's official air photographer.’ (Record by S/L. W. S. Douglas of air photography, 1915 Jan. - Mar. AIR 1/2393/240/2)

One of the biggest challenges to overcome was holding the camera steady when being buffeted by the slipstream from the aircraft’s propeller:

‘We found that, by cutting an oblong rectangular [sic] hole in the floor of the observer's cockpit of a BE 2a, the observer could, if he was not too bulky, point a camera downwards between his legs and through the aperture, and thus get a (more or less) vertical photograph. It did not occur to us to fix the camera in the floor of the cockpit; but in any case this would have been impossible, as the camera was of the folding type with bellows.’ (Record by S/L. W. S. Douglas of air photography, 1915 Jan. - Mar. AIR 1/2393/240/2)

Putting the theory into practice proved problematic:

‘We then went up to try and get some photographs of the trench system on our front. I found that the chief difficulty was that when the camera was pointed through the aperture in the floor, one could not see the ground at all, so I had to get my pilot flying on a straight and level course at the object or area that I wished to photograph; hold the camera clear of the aperture until the area to be photographed nearly filled the said aperture; and then pop my camera down into the hole and take a snap shot. This procedure was not too easy in the cramped space available, especially as the weather was cold and bulky flying kit a necessity. Each plate had to be changed by hand; and I spoilt many plates by clumsy handling with frozen fingers.’ (Record by S/L. W. S. Douglas of air photography, 1915 Jan. - Mar. AIR 1/2393/240/2)

RFC Experimental Photographic Section

Coincided with Darley’s initiative, Field Marshal Sir John French received a courtesy copy of some aerial photographs taken by the French air arm and a map on which the German defensive positions had been draw using information derived from the aerial photographs. These photographs were passed via General David Henderson, the commander of the RFC in France, to his Chief of Staff Lieutenant Colonel F. H. Sykes. Sykes had seen some of Darley’s notes on photographic mapping (The National Archives, AIR 1/2395/255/1, 3 Squadron notes on aerial photography. 1914 Dec. - 1915 Feb), and realised that the French were producing better photographs than the enthusiastic amateurs of the RFC. As a result early in 1915 Major W. G. H. Salmond, then a staff officer at HQ RFC, was tasked to liaise with the French photographic organisation. Salmond’s subsequent report outlined a highly centralised technically proficient photographic organisation being operated by the French. As a result of the report, an RFC experimental photographic section was established, by the middle of January 1915, and sent to First Wing which at the time was commanded by Colonel Trenchard. The section commanded by Lieutenant J. T. C. Moore-Brabazon had three other members; Lieutenant C. D. M. Campbell, former Sergeant now Sergeant-Major Laws and 2nd Air Mechanic W. D. Corse. Their role was:

‘. . . to report, after experience in the wings, on the best form of organization and camera for air photography.’ Jones, The War in the Air Volume 2. p. 88.

The new section’s real challenge was to build an aerial photographic intelligence aware military culture. As Moore-Brabazon pointed out:

‘It was exceedingly difficult to get anybody to appreciate what we were trying to do, or use the information we got. In fact Colonel Trenchard carried about with him photographs of the enemy trenches which he pushed before members of the army staff who only viewed them with the mildest interest inspite of the fact that they were planning attacks on the very areas about which we could give them information.’. Medmenham Collection DFG 1471, J.T.C. Moore-Brabazon, Letter to Squadron Leader Mayle, School of Photography RAF, (25 November 1959).

It would take the battle of the Somme in 1916 to finally move aerial photography from a novelty collected by Staff Officers as souvenirs to a pre-requisite for any military operation.

Moore-Brabazon and Campbell set to work on the design of a camera that could be operated in a moving aircraft. The result, the hand held ‘A’ type (Figure 5) manufactured by the Thornton-Pickard company, was first used over the German lines on 2 March 1915.

Figure 5. An ‘A’ type camera being handed to an observer of a FB5. (source: Medmenham Collection)

Operating limitations, the need to lean out of an exposed aircraft cockpit and operate a camera that required eleven distinct operations for the first exposure, and a further ten for each subsequent exposure with thick gloves or numbed fingers, combined with the need for vertical photographs for mapping purposes, led to the fixing of the camera to the aircraft. This was only possible when the key challenges of distortion due to aircraft movement and vibration caused by the aircraft motor necessitating fast shutter speeds, 1/125 of a second, were overcome. By the summer of 1915 when the ‘C’ type camera became available fixed semi-automated aerial photography had been achieved (further details on British cameras can be found in part 5).

Laws and Corse were left to operate the new Wing photographic laboratory that they improvised in a cellar under the châteaux that housed First Wing’s HQ. A process was rapidly established whereby exposed photographic plates were brought in from the RFC squadrons by despatch riders to be developed and printed. As Laws stated:

‘It was not long before a steady stream of prints were being sent to the army formations.’. Laws, ‘Looking Back’, p. 30.

In addition to establishing the Wing photographic laboratory Laws was tasked to train the pilots and observers in First Wing in aerial camera use and was also involved in the design of the A Type camera.

RFC Photographic Sections Formalised

Within the month the experimental photographic section at First Wing was declared a success and following the section’s report recommendation a photographic section was established at the HQ of each of the now three RFC Wings. The original photographic section was tasked with creating and training the new sections at the other two Wings. The new photographic sections were commanded by an RFC ‘Equipment Officer’ who was responsible for all aspects which included camera technical issues and aircrew instruction in the use of cameras. The centralisation of the photographic processing and printing at Wing level streamlined the RFC’s aerial photography processes ultimately widening the dissemination of the raw printed photograph (A ‘raw’ photograph is a photograph issued unanalysed, having yet to go through an interpretation process). The centralisation also provided another key benefit; each photographic section was charged with maintaining their Army’s History of [photograph] Coverage (HOC). The HOC comprised a record of every exposed negative which was to include; the negatives unique number, the exposure date, time and place, the exposure altitude, the atmospheric and light conditions, the shutter speed and photographic stop used. The outline of each photograph was plotted on a map and cross-referenced to a card index file system (Finnegan, Shooting the Front, pp. 46 - 47). A comprehensive, coherent and searchable HOC would prove pivotal in realising the potential of photographic interpretation; it would not be long before HQ’s at most levels began keeping records and copies of the aerial photographs that covered their areas of interest. What was lacking though was a process that facilitated an understanding of what the photographs contained. Gone was the ad-hoc approached practiced by Darley who had spent many hours at Division and Corps HQ pointing out and explaining the detail visible in his photographs to uninitiated Staff Officers. The scale of the new photographic operation made the personal approach that much more difficult. Recipients had to develop their own photographic interpretation skills and as a result during much of 1915 many recipients viewed aerial photographs as little more than very accurate maps.

The New Intelligence Source

One of the beneficiaries of this new intelligence source was Lieutenant Colonel J. Charteris, General Staff Officer (GSO) I Intelligence at First Army HQ. Aerial photographs had been coming into First Army Intelligence in slowly increasing numbers since the start of the year. In a diary entry dated February 24 1915, probably during the planning for the battle of Neuve Chapelle, he wrote:

‘My table is covered with photographs taken from aeroplanes. We have just started this method of reconnaissance, which will I think develop into something very important.’. John Charteris, At G. H. Q. (London, Cassel &Company, 1931). p. 77.

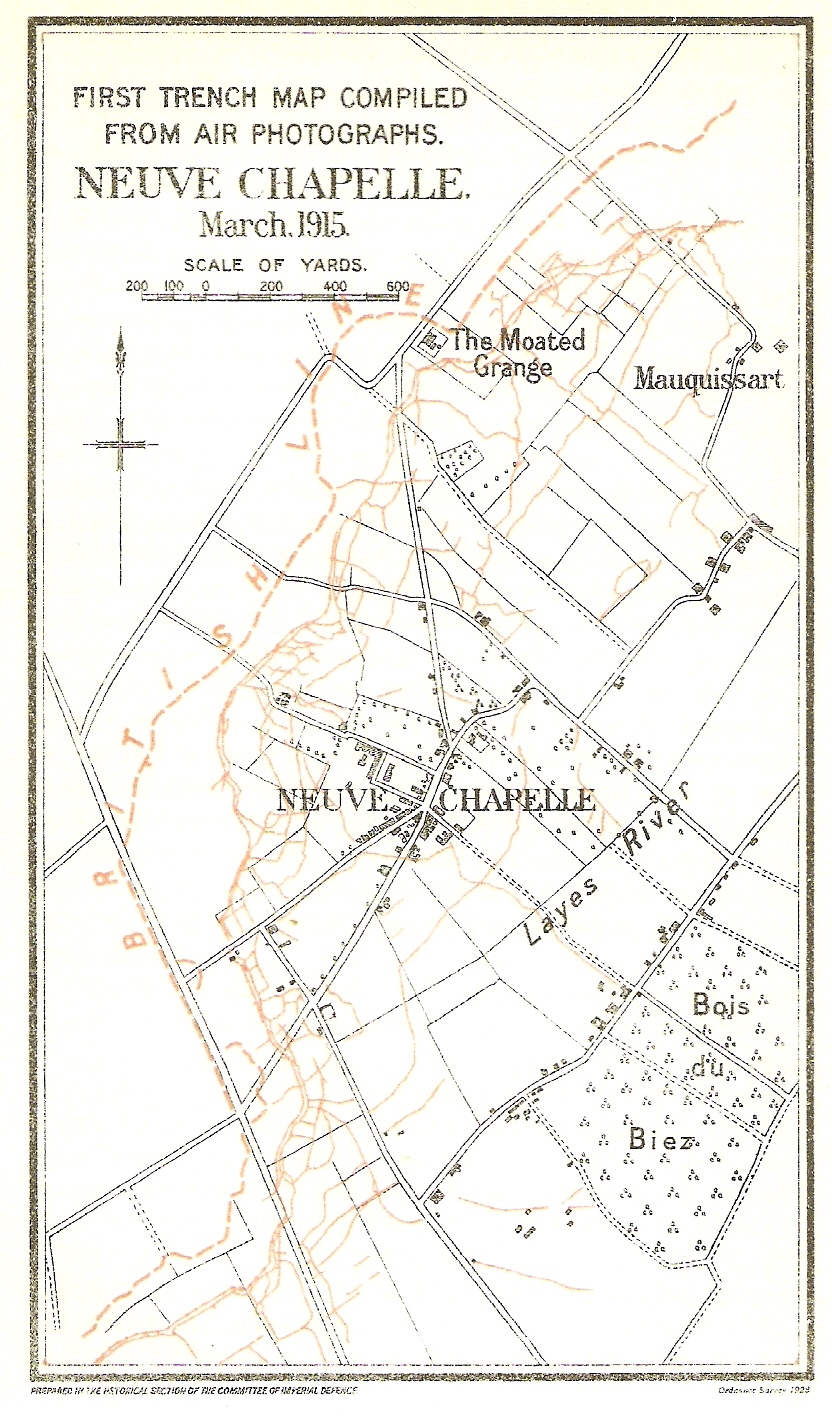

At this stage of the war the mapping of areas behind the German lines was the responsibility of the Intelligence staff. The techniques of revising detail and plotting German defences from aerial photographs onto the available maps had been developing over the previous months and by the end of February the RFC’s pioneering photography work coupled with Laws’ camera training had enabled First Wing, presumably mainly Darley and Douglas to photograph the entire German trench system in front of First Army to a depth that ranged from 700 to 1,500 yards. The result was a fairly complete picture of the German tactical dispositions. This tactical picture, which was regularly updated, was used by Haig to plan the Battle of Neuve Chapelle. Significantly photographic interpretation inputs from Darley prompted modifications to First Army’s attack planning (J. Laffin, Swifter than Eagles: A Biography of the RAF, Sir John Salmond (London: William Blackwood, 1964), p.60-61.) Additionally 1,500 copies of a 1:5,000 scale map, derived from these photographs, overlaid with an outline of the German defensive system were specially printed and issued to each of the attacking Corps (Figure 6). Crude compared to later standards (see Figure 8) the maps represented the first true Common Operating Picture (COP) ever taken into battle by a modern British army.

First Army was the first to recognise the real utility of aerial photography for intelligence purposes: ‘in spite of limitations, aeroplane photographs are, at the present state of proceedings, by far the most reliable evidence we get of alterations in the enemy’s line and indications of his future moves’. No.32 ‘IM’, First Army to Moore-Brabazon, 1 June 1915, Box 87, Moore-Brabazon Papers, RAFM

Figure 6. Neuve Chapelle 1915. (source: H. A. Jones, The War in the Air Volume 2 (Oxford, Clarenden Press, 1928) between pp. 90-91.)

Artillery Driven Synergy of Ground Survey, Cartography and Aerial Photography

Although a resounding success the Neuve Chapelle battle map was not the trigger that moved aerial photography from the status of novelty to indispensability. From late 1914 through all of 1915, the British Army experienced a critical shortage of artillery ammunition. This shortage drove the introduction of artillery survey; battery positions and targets needed to be fixed to a survey grid so that rounds used for target ranging and registration could be kept to a minimum. From early 1915 an artillery driven synergy of ground survey, cartography and aerial photography which resulted in the production of maps on which German positions and activity could be accurately plotted and subsequently targeted was begun.

The first use of a squared map prepared by Lieutenant D. S. Lewis of the RFC was noted in September 1914 during the initial attempts to control artillery fire from the air using wireless (Jones, The War in the Air Volume 2, p. 85.). By the end of 1914 the squared map system had been accepted and adapted and covered the whole of the British front. The co-ordinate system used allowed positional locating accuracy down to approximately five yards, assuming that the base mapping was accurate. It was soon recognised however that the Army Intelligence Sections lacked the necessary skills to produce mapping to the required levels of detail or accuracy.

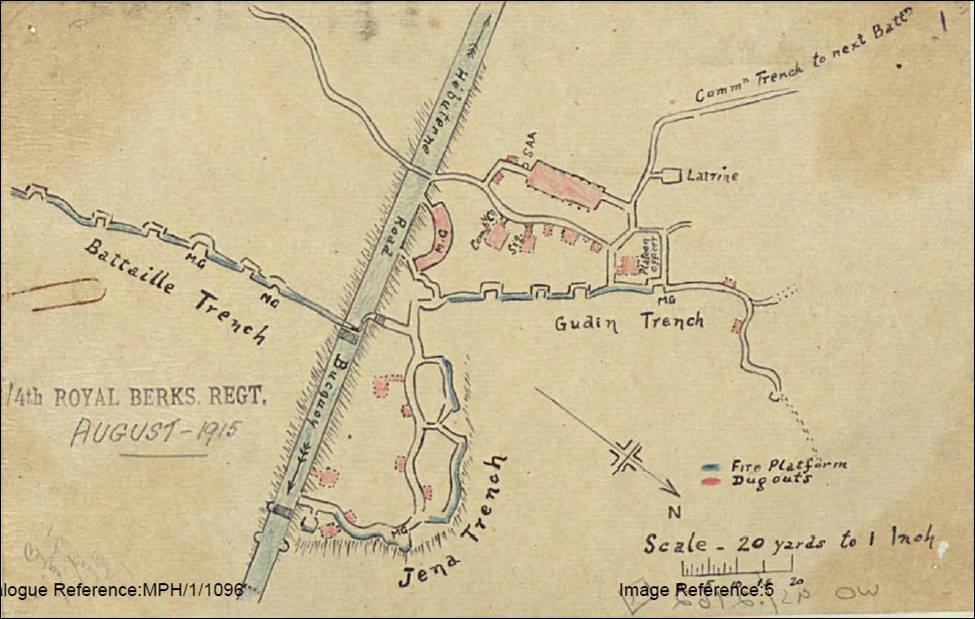

Figure 7. Hand drawn by ‘Intelligence’ - (source: National Archives extracted from WO 95/2762.)

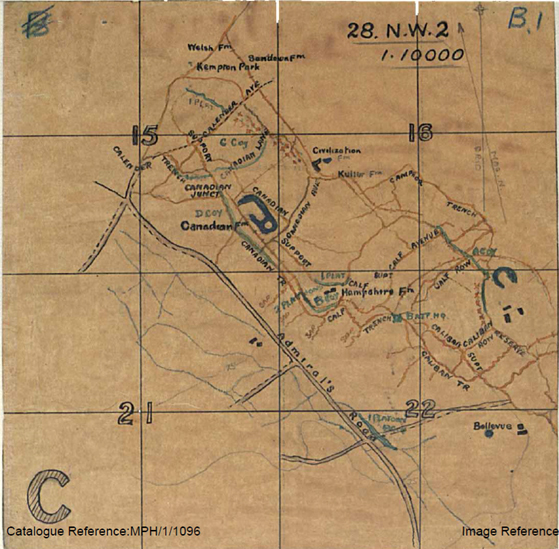

So between July and September 1915 Topographical Sections were created at Army level. These sections were responsible for all survey work, map supply and reproduction in their Army area. This included the production of trench mapping from aerial photographs.

Figure 8. First generation 1:10,000 trench map - (source: National Archives extracted from WO 95/2762.)

The transfer of ‘maps and printing’ from Army Intelligence to the Topographical sections was not seamless. According to Capt Carrol Romer, the officer in charge of First Army’s Maps and Printing Section in early 1915, who has been credited as the first British photographic interpreter whilst serving under Charteris (Charteris, At G. H. Q.. p. 82.):

‘Masses of information of all sorts is collected at great labour and expense and it all goes onto a file and there it is comfortably and peacefully disposed of.’ Romer diary, quoted in: (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers,p. 86.)

Romer was referring to perceived shortfalls in the effective compilation and dissemination of counter-battery intelligence during the transfer. Whilst the Army Intelligence Sections remained the authority on the strength and dispositions of the enemy the topographical evidence supporting that intelligence, much of it derived from the ever increasing numbers of aerial photographs, had to be plotted accurately onto the map. As a result the bulk of the photographic interpretation work shifted to these new Army Topographical Sections with any ambiguities being referred to ‘Army Intelligence’ for clarification. By the end of 1915 Third Army’s Topographical Section, at the request of the Army Staff, had begun to include the German trench system, including barbed wire, and known German artillery battery positions as overlays on the newly created 1:10,000 map sheets.

Uneven Development of Photographic Interpretation Skills

Despite this cartographically driven shift, the ever increasing number of aerial photograph recipients in the army’s subordinate formations continued an ad-hoc and uneven development of their photographic interpretation skills. During the summer of 1915 Alan Lloyd was appointed as an intelligence officer on the staff of First Corps where he was made responsible for the Corps aerial photographs ‘. . . which at the time, were merely regarded as very accurate maps.’ (Medmenham Collection DFG3412, Letter Lloyd to Babingdon-Smith, 3 Dec 1957.). In November 1915 Lloyd gave a lecture on aerial photographs to his Corps Commander which proved such a success that he was ‘sent round troops at rest to teach them how to read their photographs.’ (Letter Lloyd to Babingdon-Smith, 3 Dec 1957.). Lloyd went on to produce a series of notes to support his photographic interpretation lessons that were ultimately sent to GHQ, via Corps and Army, and were reproduced as the first British photographic interpretation guide ‘S.S. 445 Some Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs’ in November 1916 (The National Archives, AIR 34/735, Some Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs (December 1916). Referenced in ‘S.S. 550 Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs’, March 1917.). In contrast the Canadians appeared to have had a far greater awareness of the utility of aerial photographs during 1915:

‘A German aeroplane has been hovering over our positions looking for my gun, so we have stopped firing and all movement. I know just how the chicken feels when the hawk hovers over it. Few people realize how much aeroplanes figure in this war, for war would be much different without them. They do the work of Cavalry only in the sky. Whenever they come over, the sentries blow three blasts on their whistles and everybody runs for cover or freezes; guns stop firing and are covered up with branches made on frames. If men are caught in the open they stand perfectly still and do not look up, for on the aeroplane photographs faces at certain heights show light; dugouts are covered over with trees, straw or grass. We use aeroplane photographs a great deal; they show trenches distinctly and look very like the canals on Mars.’ Louis Keene, “Crumps” The Plain Story of a Canadian Who Went, (Boston and New York, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1917) pp. 83-84.

When the Canadian Corps formed in September 1915 they established a new GSO, Second Grade, to command the intelligence service within the Corps. This officer had under his command:

‘. . . a small force of draughtsmen and assistants working on aeroplane photographs, which were then beginning to be used extensively . . .’. J.E. Hahn, The Intelligence Service within the Canadian Corps 1914-1918,(Toronto, Macmillan, 1930) p. xviii.

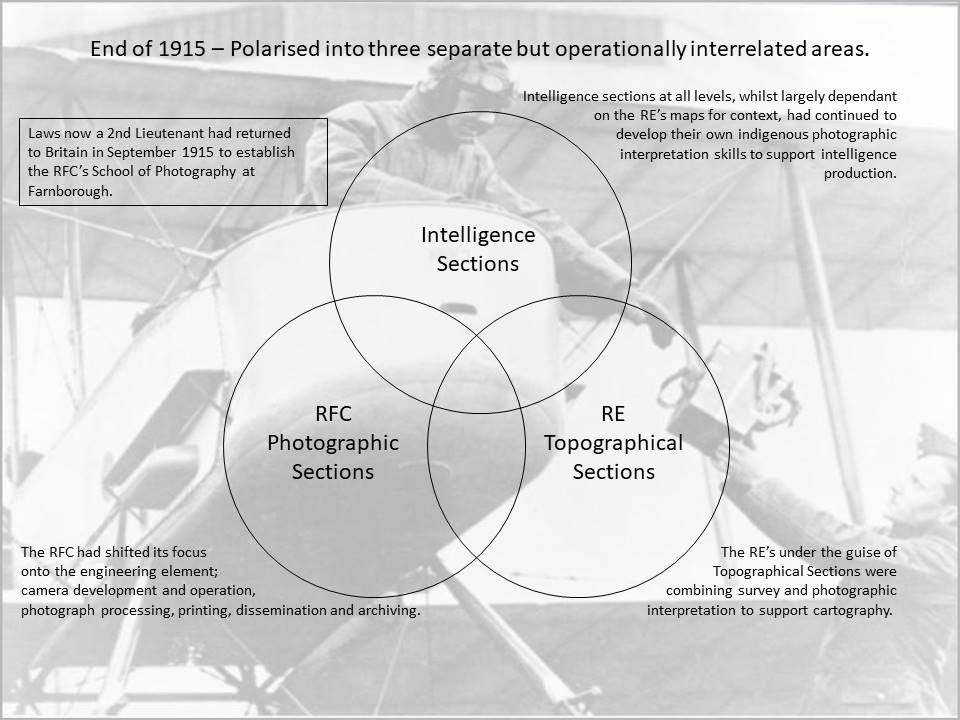

By the end of 1915 aerial photography had polarised into three separate but operationally interrelated areas (Figure 9). The RFC had shifted its focus onto the engineering element; camera development and operation, photograph processing, printing, dissemination and archiving. Laws now a Second Lieutenant had returned to Britain in September 1915 to establish the RFC’s School of Photography at Farnborough. The RE’s under the guise of Topographical Sections were combining survey and photographic interpretation to support cartography. Intelligence sections at all levels, whilst largely dependent on the RE’s maps for context, had continued to develop their own indigenous photographic interpretation skills.

Figure 9. Aerial photography had polarised into three separate but operationally interrelated areas.

Part 1 - The Pre-Cursor 1849 to August 1914Part 2 - The Beginnings August 1914 to January 1916

Part 3 - Aerial Photography comes of age

Part 4 - The Uses for Aerial Photography

Knowledge Version 2 1.1